In late 2010 a revolt of the poor and unemployed broke out in Tunisia. Within a few short months the rebellion had spread, with earth-shattering effects, to Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain, Libya, Syria, Oman, Iraq and other countries. This inspired the movement of square occupations in Spain and Greece, and even spread to the USA with the occupation of the capitol building in Madison, Wisconsin and later the Occupy movement.

Something similar, but on a much bigger scale, took place after the First World War. In February 1917 hordes of Russian soldiers joined the workers of the cities in revolt and overthrew the Tsar. The Soviets, councils of directly-elected workers, peasants and soldiers, grew in strength . In November the world’s first successful socialist revolution was consummated as the soviets, led by the Bolshevik Party, seized power from the short-lived bourgeois government. The effect was electric: within months a million German, Austrian and Hungarian workers were on strike against the war. This initial revolutionary wave battered against the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, but was beaten back.

. In November the world’s first successful socialist revolution was consummated as the soviets, led by the Bolshevik Party, seized power from the short-lived bourgeois government. The effect was electric: within months a million German, Austrian and Hungarian workers were on strike against the war. This initial revolutionary wave battered against the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, but was beaten back.

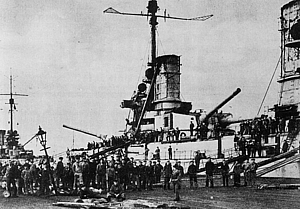

In October and November 1918 the assault began again with renewed force. German sailors refused to go out on a suicide mission, and  instead seized control of the ships from their officers. The sailors marched with the red flag into coastal cities and revolution spread uncontrollably throughout Germany. Soviets controlled Berlin and most major cities. The war ended and the Kaiser fled to Holland. The Austro-Hungarian and German Empires followed the Russian Empire into oblivion.

instead seized control of the ships from their officers. The sailors marched with the red flag into coastal cities and revolution spread uncontrollably throughout Germany. Soviets controlled Berlin and most major cities. The war ended and the Kaiser fled to Holland. The Austro-Hungarian and German Empires followed the Russian Empire into oblivion.

Civil war was raging in Russia. Britain, France, the USA, Japan and other countries intervened with thousands of troops and staggering amounts of money to prop up the White Armies who fought to restore the old regime. But British workers refused to carry weapons destined for use against Russian workers. French sailors in the Black Sea, sent there as muscle for the Whites, took over their ships, raised the red flag, shelled the Greek troops that tried to stop them, and set sail for home.

In 1919 and 1920 civil war conditions in parts of Europe mirrored on a smaller, more dispersed scale the civil war in Russia. Bavaria and Hungary became socialist Soviet republics and had to fight with bullets for every month of their short lives. Germany saw years of battles, uprisings and coups.

In Italy the “Biennio Rosso” saw revolutionary land seizures in the south and factory occupations in the north. In Spain general strikes, struggles on the farms and bombings and shootings defined the “Bolshevik Triennium” of 1918-1920. A radical peasant government came to power in Bulgaria, shoving aside the old military-aristocratic rulers.

South Africa, Australia, Argentina and Peru saw strikes and social conflicts on a huge scale. The United States saw the Seattle general strike,

the Boston Police strike and the colossal steel strike in Pennsylvania and Indiana. In Canada syndicalist workers took over Winnipeg.

The May Fourth movement in China saw mass protests of young people and gave birth to the Chinese Communist Party. Communist revolutionaries took power in Mongolia.

In England massive strikes took place alongside mass army mutinies. One mutiny saw British soldiers establish a “soviet” in a French coastal town. Strikes in Glasgow reached such intensity that crowds of workers battled police in George Square – and won. Union leader Willie Gallacher downed a police chief with a perfect punch to the jaw. Against the soldiers’ soviet and against Glasgow the British government had no alternative but to send in tanks and troops.

The British Empire stood on the edge of an abyss. Faced with revolution in Egypt, it resorted to killing thousands of people. In India, a general strike led a British officer to massacre hundreds of peaceful protestors in Amritsar.

Ireland

Amazingly, many of those who write about Europe in this period leave Ireland out of this story or else deny that there was much connection. On the other hand most Irish historians entirely ignore the international context to Irish events. But Ireland is in fact a very good case study in this global revolutionary wave, having all the key elements: local and national general strikes, massive industrial and agrarian unrest, syndicalist militancy, mass demonstrations, civil disobedience, factory occupations, imperialist and anti-imperialist violence, a movement for self-determination and a civil war.

The Leaders of the Labour Movement

In the 19th century the capitalist class transformed the world. In Europe and North America industrialisation created massive cities, concentrated working classes and a new abundance of wealth. As the century went on free enterprise gave way inevitably to gigantic monopolies. Capital chased new markets and resources, and the flag and the gun followed, subjecting all the world to the rule of the few advanced capitalist countries.

The working class internationally was becoming more and more organised and militant. Their industrial and political rise brought to prominence a privileged layer of leaders, bureaucrats and politicians who were more interested in compromise than struggle, who believed (conveniently for them and their cosy positions) that progress toward socialism and working-class emancipation must be slow, gradual and within the framework of the bosses’ laws and in the political arena dominated by the rich.

In the years before the outbreak of the First World War trade union membership and power grew impressively, driven by the “New Unionism” of militant tactics and socialist politics, in defiance of the growing bureaucratic stagnation. In England this found its expression in the “Great Unrest”; in Ireland it appeared in the form of 1907 Belfast strike and in the 1913 Dublin lockout.

Then came the war. Bloody fighting raged on the frontlines, consuming millions of human lives, but in the hungry cities and villages an oppressive peace reigned between the worker and the boss.

The labour movement split in two with the declaration of war. The majority of the leaders of the socialist, labour and social-democratic parties all over Europe sided with their own governments in the war.

In 1917 Paul Lensch, a German social-democratic parliamentarian, wrote of “World-Revolution” – but not with the meaning you might expect. For him the World War was not the prelude to world revolution – it was the world revolution! It represented “the overthrow of the English world domination by the Germans”. He compared this to the overthrow of the Roman Empire by “the Germans” 1500 years before. The idea of the right of peoples to independence was just “individualistic international anarchy”. Germany would triumph, “and then will dawn a new epoch for humanity.” And after all, Lensch makes clear, the more Germany wins in the war, the more spoils there will be to divide between labour and capital.[1]

Lensch stated the case more nakedly and blatantly than others dared. However this was the basic attitude of most of the labour leaders of all the combatant countries. Exceptions included the Bolsheviks in the Russian Empire and the far weaker labour movement in Ireland. But the British Labour Party, the French Parti Socialiste and the vast majority of the leaders of the German SPD betrayed the pledges they had made to resist war through general strike action. Their country was exceptional and had great things to offer the world – by conquering it. Victory (which they all saw as inevitable for their side) would bring the spoils of the war home to the working class.

Leadership in Revolution

The extent of enthusiasm for the war has been greatly exaggerated. In any case the apparent pro-war consensus was shattered in the closing years of the war, especially from 1917 onward. As we have described, the working class rose up repeatedly with tremendous energy and organisation. But they were saddled with an utterly bankrupt leadership, the same that had led them into the war.

In November 1918, hundreds of thousands thronged the streets of Berlin and soviets ruled many cities. From one balcony the revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht was declaring a soviet socialist republic; from another balcony nearby the social-democrat Ebert was

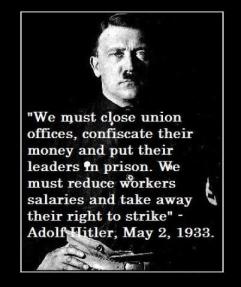

anxious to steal a march on Liebknecht, and declared a republic. The masses still trusted their old leaders, and thought they offered the surest path toward socialism; in reality, social-democrats like Ebert, Scheidemann and Noske were making deals behind the scenes with bosses and proto-fascist militias to stave off revolution even at the cost of thousands of lives. In this way the advocates of “gradual” reforms toward socialism handed over the initiative to the far right and prepared the way for the triumph of fascism in Germany.

In Italy likewise the Socialist Party failed to take the initiative when, in 1920, workers ruled thousands of factories. Again, the initiative passed to the right. Mentally unstable and sadistic individuals formed death squads and spent their nights high on coke beating up and killing socialists and workers’ leaders. Funded by industrialists, with a vanguard of special forces veterans, these “combat groups” used brute force to beat the life out of the Italian revolution. Their leader, an ex-socialist crank named Mussolini, became the fascist dictator of Italy, the first in the world, in 1922.

Austrian Social-Democratic leader Otto Bauer described the great demonstrations that rocked Vienna day after day in 1919: “Every newspaper brought news of the struggle of the Spartacists in Germany, every speech gave information of the glorious Russian Revolution, which by one stroke had put an end to all exploitation. The masses who had recently witnessed the downfall of a strong empire had no suspicion of the strength of the Capitalist Entente. They imagined that revolution would spread like wildfire through the victorious countries. ‘A dictatorship of the proletariat!’–‘ All power to the Soviets!’–nothing else was heard in the streets […] Peasants had also returned home from the trenches full of hatred for war and militarism, for the bureaucracy and for the plutocracy [… ] Together with the proletariat they imagined that the political revolution must needs bring with it a revolution with respect to property ownership.” (http://www.marxists.org/archive/james-clr/works/world/ch04.htm)

CLR James points out that the same Otto Bauer who describes so vividly this revolutionary situation did everything he could to dampen and defuse it. The Social-Democrats, brought into a new government, refused guns to the Hungarian Soviet Republic, arrested the Austrian Communist leaders and shot down workers who protested demanding their release. Absurdly conservative, the Austrian social-democratic leaders refused to be so bold as to call for freedom for the oppressed nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until after that Empire had collapsed, and self-determination was an established fact!

In James’ words, the post-war years saw “the new Socialist order striving to be born all over Europe, and a thin scum of bureaucrats with the ear of the masses holding up the historical process and throwing humanity a generation back.” (http://www.marxists.org/archive/james-clr/works/world/ch04.htm)

History doesn’t move at a pace set by comfortable labour bureaucrats. When revolutionary situations arise, you can’t wish them out of

existence and go back to the slow accumulation of inoffensive reforms. A year of defeats can undo a half-century of slow methodical organisation. A year of decisive, strong, revolutionary leadership, as demonstrated in 1917 in Russia, can end with the working class in power. On the other hand, given half a chance, the bosses play their trump card, fascism, which uses ultra-nationalism, male action-hero attitudes and violence to crush the power and organisation of the working class.

The Verdict on the World Revolution

This was the dark, tragic side of the World Revolution. Its successes are obvious: they include establishing the world’s first workers’ state and planned economy in the USSR, ridding the world of four rotten monarchies, self-determination and universal suffrage in many countries, and ending the war. But its failures, which are the responsibility of the social-democratic leaders of the day, led to the triumph of counter-revolution. In Germany, Italy and Spain this took the form of fascism.

Within a hungry, backward, isolated Russia the reaction took shape as Stalinism. This represented a privileged layer of managers and bureaucrats who maintained their power by slaughtering and starving peasants, national minority groups and all those who stood for the real tradition of the Russian Revolution. They forever stained the name of Marxism, socialism and communism by covering their crimes with a paper-thin layer of justification in the language of the revolution.

Historical phenomena aren’t 90-minute feature films. They don’t end neatly with an unambiguous triumph for a clearly-defined set of sympathetic characters. Fanciful historians always counterpose to the hardship and suffering of revolution some imaginary form of government called “liberal democracy”. The countries they refer to, France

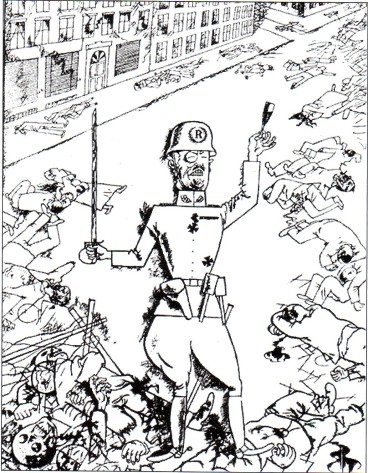

The slaughter of revolutionaries by reactionary army officers, captured in this contemporary cartoon

and Britain, were viciously class-divided societies which ruled over vast empires whose subjects enjoyed few democratic rights and suffered famines comparable to those that happened under Stalin.

In any case an advanced capitalist society is not an appropriate “control” from which to judge the success of a revolution in a vast semi-feudal empire. We have no such “control” in the colossal experiment that is revolution.

Ireland

Pivotal moments in Irish history tend to mirror global events. The 1798 rebellion was fought under the slogans of liberty, equality and fraternity. The 1948 Republic of Ireland Act came, not by accident, during the period of a great international strike wave, the establishment of the welfare state, independence for India and the Chinese revolution. The 1968 Civil Rights movement in Northern Ireland took its inspiration from the struggles of African-Americans.

Similarly, in the revolution of 1917-1923 strange words like “Bolshevik” and “Soviet” acquired immense significance. In the chapters to follow we will show how the Irish Revolution mirrored the World Revolution in its successes and its failures, in the wasted potential for the socialist transformation of society, and in the role of leadership.

In Ireland, too, a “thin scum” of labour leaders held back history through subordinating the working class to nationalism. Thus the Irish Revolution on the one hand shows the enormous power and potential of the masses led by the working class. On the other hand it shows how when a revolutionary situation arises, it’s not good enough for the working class to be led by alarmed, conservative bureaucrats and naive, well-meaning improvisers. Those who want to see a socialist world must organise themselves before time into a conscious revolutionary organisation, win the trust of the working class through being the most determined and skilful fighters, and grow through uncompromising political debate and discussion.

In a revolutionary crisis such a party would be posed as an alternative leadership, capable of leading the masses to a historic breakthrough. The Arab Spring, events in Egypt, Turkey and Brazil during the summer, and the developing crisis and struggle on the peripheries of Europe and in the USA, show that talking about revolutions is not just a matter for history buffs. A revolutionary party of the working class is the key missing ingredient in all these situations. The reader can take what lesson they want from the chapters that follow, but for the author the lack of organised revolutionary leadership is as obvious in Ireland in 1919 as in Greece in 2013.

[1] Paul Lensch, Three Years of World-Revolution, Constable, London, 1918